Interfaith and the Worldwide Krishna Movement

Interfaith and the Worldwide Krishna Movement

Dr John Fahy reflects on the theme of interfaith at a recent conference at Harvard University.

Last week I was invited to present a paper at a multidisciplinary conference entitled The Worldwide Krishna Movement: Half a Century of Growth, Impact and Challenge. This conference, held at Harvard University's Centre for the Study of World Religions was convened to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the founding of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness or ISKCON (and was organised by devotee-scholars). Although certainly not the only 'Krishna Movement' to emerge in the 20th century (nor the only religious tradition to make the journey from East to West at the time), ISKCON's worldwide success is unprecedented in the history of the Vaishnava tradition to which it traces its roots. Thanks to their colourful proselytising style ISKCON devotees became a common sight on the streets of America in the 1960s and 70s (and are still recognised by many today as those saffron-clad, Bhagavad Gita-wielding Hindu missionaries who give out free food at SOAS). While in the early years ISKCON was known to academics as a 'New Religious Movement' (or to everyone else as a 'cult') with a 'world-rejecting' agenda, it has transformed during its short history into what could be described today as a diverse 'world-accommodating' movement that looks to engage with, rather than retreat from, the world. As this conference made clear, ISKCON's efforts in the fields of both academics and interfaith are widely held to be indicative of the movement’s maturation.

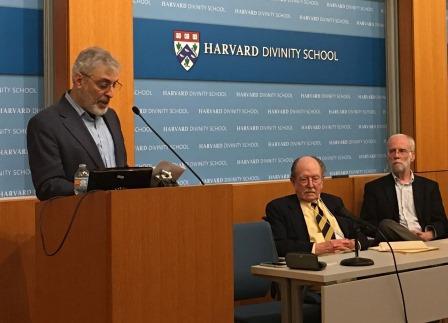

Professors Graham Schweig, Thomas Hopkins and Francis Clooney (Photo credit: Krisztina Danka)

Professors Graham Schweig, Thomas Hopkins and Francis Clooney (Photo credit: Krisztina Danka)

Over the course of three days, papers were distributed across panels on history, sociology and theology, amongst other themes. In attendance were scholars (who have spent their careers working on various aspects of the movement), devotees (who have spent decades in the service of the movement), and long-time friends of ISKCON, such as Muslim scholar Professor Sanaullah Kirmani, who recalled his impressions of ISKCON founder Srila Prabhupada's lecture in the very room we were sitting (back in 1968). Also in attendance was the director of the Oxford Centre for Hindu studies, Shaunaka Rishi Das (whose own efforts have been foundational to ISKCON's interfaith engagement in the UK) and director of Harvard's Centre for the Study of World Religions, Professor Francis Clooney. Papers addressed a diverse range of topics, and engaged with centuries of theological development, from late 19th century Vaishnavism in Kolkata to education in ISKCON today. My paper, 'Theology, Ethics and Community', based on my PhD research on ISKCON in West Bengal, India attempted to account for the pervasiveness of sentiments of isolation and loneliness in ISKCON by asking what theological resources devotees are presented with in the pursuit of a devotional community. While interfaith emerged as a surprisingly prominent theme over the three days, there were two papers presented that dealt explicitly with ISKCON's interfaith efforts.

The first of these papers was devotee and scholar Dr. Ravi Gupta's 'Towards an Interfaith Theology for ISKCON'. In this paper, Gupta turned to Vaishnava history for a blueprint for contemporary interfaith engagement. He recounted a particularly famous example of a heated disagreement between Caitanya Mahaprabhu (the 15th century avatar of Krishna) and a local Muslim magistrate in Bengal (in what was Mughal India). The disagreement arose after the magistrate, apparently angry at Caitanya's increasing popularity, declared the chanting of Krishna's name illegal, and smashed a drum that was used to accompany Vaishnava devotional hymns. After an initially threatening response from Caitanya (leading his devotees on a march to the magistrate's house), a dialogue ensued during which Caitanya defuses the situation by defeating the magistrate with logic. The magistrate then submits to Caitanya and gives his word that from that day on his devotees would no longer be persecuted and were free to chant the names of Krishna publically. Although there are some disquieting details in the story (including undertones of violence and conversion), for Gupta this encounter demonstrates what he called an 'informal theology of dialogue', within which Vaishnavas can find all the tools necessary for meaningful engagement with people of other faiths. Gupta related the ultimately peaceful outcome of this encounter to the inclusivist tendencies inherent in the tradition, and argued that this story should be treated as a blueprint for Vaishnava-other interfaith dialogue. At the same time however he offered some important caveats, in particular highlighting the dangers of triumphalism (Caitanya, after all, clearly comes out on top), which as he correctly pointed out, would today only serve to burn rather than build bridges.

The second paper to deal with the theme of interfaith was presented by Professor Gerald Carney. Although not an ISKCON devotee, Carney has long been a friend of the movement and has been a prominent figure in bringing Vaishnavas and Christians together for interfaith dialogue. His paper 'Krishna Consciousness at the Interfaith Roundtable', a reflection on his experience as a Christian scholar whose research focuses on Vaishnavism, detailed developments in, and details of, such interfaith initiatives. In 1998 ISKCON began engaging in Vaishnava-Christian interfaith sessions in Washington (and Vaishnava-Muslim dialogues began in 2010). These were formative years as in 1999 ISKCON published an essay entitled 'ISKCON's Statement on Relating with People of Faith in God' written by Shaunaka Rishi Das). This essay would form the basis for what could be thought of as ISKCON's own Nostra Aetate, or institutional guidelines on interfaith relations. As Carney outlined, ISKCON has continued to reach out and has just recently completed its second annual interfaith conference in Tirupati, India. Carney spoke of the benefits not only of talking together, but of praying together, presenting and discussing each other's symbols and focusing on central themes that the traditions share ('love of God' being one recent example). He emphasised the importance of personal relationships, without which, he insisted, such dialogue sessions would not be possible.

While I was surprised at how often the theme of interfaith emerged throughout the conference, perhaps the most striking testament to ISKCON's maturation was not in its reflection on or engagement with other religious traditions, but in its openness to share the space created for its 50th anniversary celebration with outsiders (me included). In the spirit of interfaith, and to some extent against ISKCON’s commitments to its own tradition, conference organisers invited former Head of the British Council of Churches' Committee on Interfaith, and Methodist minister Reverend Dr Kenneth Cracknell, to close the conference with a prayer. What would have been considered an act of blasphemy in the early years of the movement, it seems, is today welcomed as a blessing.

This article is written by Dr John Fahy who is a Junior Research Fellow at the Woolf Institute. Based in Qatar, John is part of the QRNF-funded project assessing the effectiveness of interfaith initiatives in Doha, Delhi and London. Details of the project can be found here.

Back to Blog